Introduction

Aswan (Syene) is located on the east bank of the Nile, at the First Cataract, so it can be considered a frontier town that nowadays, as in antiquity, marks the southern border of Egypt. The history of the site, the southernmost city of the Roman Empire, is strictly linked to that of Elephantine, the small isle in the Nile in front of Aswan, that was a military, religious and economic centre. Aswan, on the other hand, famous in antiquity for its granite deposits, functioned mainly as a trading centre, a garrison town and an important episcopal see, from the IV century CE.

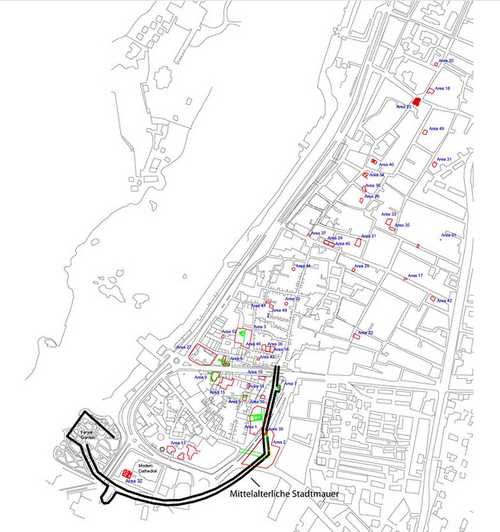

The history of the excavations in Aswan was conditioned by the partial overlap between the southern part of the modern town and the ancient one, so that few monuments are visible today. The two main buildings are the Ptolemaic temple of Isis, converted into a church, and the Domitian temple, found in 1921. Three main phases, all rather recent, can be identified in the systematic archaeological researches at the site: in the 1970s an Italian équipe led by Edda Bresciani worked in the area of the temple of Isis; between the 1970s and the 1990s started the project supervised by the director of the Swiss Institute, Horst Jaritz, which expanded the excavations to other areas, such as the temple of Domitian and the church of St. Psoti and deepened the investigations around the temple of Isis (1987-1993); since 2000 has been underway a joint project of the Swiss Institute and Supreme Council of Antiquities, led by the current Director of the Swiss Institute, Cornelius von Pilgrim. The Swiss-Egyptian mission is conducting large-scale research which has brought to light several archaeological sites, sometimes explored in emergency conditions, as well as a further deepening of the areas around the temple of Isis and Domitian.

The oldest traces of settlement found so far in the area north of the Greek-Roman city date back to the Old and Middle Kingdom, when the evidences also extend further east. From the Persian period and the 30th Dynasty archaeological data is much richer. Probably already in the New Kingdom the city begins to be structured, in connection with a fortress directly south of the settlement, and to équipe itself with a fortification wall (a stretch of it is visible just east of the temple of Isis). Hellenistic Syene expecially flourished at the beginning of the 2nd century BCE, when the oldest city wall was largely destroyed, and the settlement area enlarged to the south. In area 15 a larger building with a bathroom was erected above an unfinished Ptolemaios III monument.

The main monuments of Roman times are the so-called Temple of Domitian (area 3) and the "Roman Shrine" (area 5, a Doric style building discovered in 1999, as well as some traces of a temple of Tiberius (area 2). The presence of a Roman basilica (2nd c. CE) is suggested by several granite columns. In Roman times Syene was an administrative and military centre, housing a garrison with three auxiliary units, even though archaeological traces of this military presence are few. A great deal of data on Roman Aswan comes from excavations in the necropolis. For Late Roman and Byzantine times there are few architectural traces, except for a church with martyrdom and baptistery (area 6), which confirms the growing importance of Aswan as a Bishop’s seat.

In addition to the church in the temple of Isis, other Christian buildings have been identified: the church mentioned in PSBA 30, 1908, which was thought to have been built as a result of the conversion of the so-called temple of Ptolemy IV and the medieval Church of Saint Psoti, demolished in 1966 and then reconstructed (Jaritz 1985) as a 4-column stone building of Nubian type, in front of the north-western corner of the roman castrum (for an overview of Syene Christian churches, see Djkstra 2008, pp. 96-110, with bibliography). In early Islamic era the city became the most important station for North African pilgrims on their way to Mecca and the urban area extended northwards. An Islamic fortification, built with reused blocks from a temple of the 30th dynasty, partly destroyed during the construction of the modern Coptic cathedral in area 32.

Of great importance are the documents collected in the "Patermouthis archive" (32 Greek and 6 Coptic papyri, and many other fragments), dating from 493 to 613 CE, that record information about a man born in Syene, that worked as a boatman and then as a soldier in the regiment of Elephantine (Dijkstra 2008, pp. 65-78).

Temple of Isis

Pharaonic Period

The only testimonies relating to the Pharaonic period, however uncertain, concern the discovery during the excavations of the Italian mission of 1970-1971 of some erratic blocks with decorations and hieroglyphic inscriptions. They seem to be pertinent to the structure of a monumental gate in which King Nectanebo II of the XXX dynasty appears in the act of making offerings to divinities of the Egyptian pantheon. It could therefore be an attestation of the construction of a place of worship, or of an existing building, located around the Ptolemaic temple of Isis (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, p. 305). However, it is not excluded that the blocks bearing the name of Nectanebo II may have come from Elephantina, and that they were transferred to Aswan by the Turkish authorities to build military warehouses. Finally, accepting the hypothesis of their coming from Elephantina, it can also be assumed that they were found in various places of the city during the excavations conducted by the Director of the Museum of Upper Egypt el-Hetta in 1961-1963 and that they were then collected in the Isis temple area (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, p. 308-309).

Architectural elements not in situ

Blocks with hieroglyphic inscriptions and decoration (XXX Dynasty) (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, pp. 159-163, nn. 1-6).

Hellenistic Period

The temple of Isis, a small but completely preserved Pharaonic temple, was discovered in 1871 during works for the construction of the railway network and the following year the plan of the building was published by M. Mariette , with the inscriptions and reliefs of the identified structure. More accurate investigations were carried out about a century later (1970-1971) by the Italian mission coordinated by E. Bresciani and S. Pernigotti, which completed the excavation of the building's floor level and published the relative documentation, drawings of the decoration and a complete ground plan. Since 2000 the archaeological investigation at the temple of Isis area is part of a larger excavation project at Aswan carried out by a Swiss-Egyptian, still ongoing. The team is moreover involved in a second project which aims at collecting and publishing the 352 graffiti identified so far on the structures of the temple.

Found at a depth of 8 m compared to the ancient kom, the temple is inserted between some houses of the Byzantine era and is partly obliterated by the additions of the modern city. At the time of the discovery, the building, which originally had to be included in the city walls enclosure, preserved the structures of the central nucleus (naos), the hypostyle hall and the external pillars. Based on the inscription identified during the archaeological investigations, the building was commissioned by Ptolemy III Euergetes I (246-221 BCE) and saw contributions from Ptolemy IV Philophator (221-204 BCE) and later from Ptolemy X Alexander I (107-88 BCE).

The temple, today still standing, is oriented NW-SE and is built of sandstone blocks on the walls and stone slab floor, while the roof was made of large stone slabs approx. 1 m wide, arranged like the orientation of the building. It presents a total length of 19 m, a width of 15 m and a height of up to 7 m. The decoration has remained unfinished since they are present only in correspondence with some of the main parts of the building. At the centre of the external facade the main portal opens; it is decorated with figurative scenes in relief and texts and is surmounted by a frame with a winged solar disk in the centre. At the time of the Italian excavations, it conserved evident traces of polychromies in blue, red, green and yellow, particularly well preserved on the architrave. On the south side of the building a secondary door opens, smaller than the main one, decorated on the architrave and on the side jambs; also, in this case it is characterized by a frame with ruined winged disk, but with traces of polychromies. Inside the construction, almost half of the entire width is occupied by the pillared hall. The pillars are square (1.80 m per side), without bases, and support a granite architrave. The room is not decorated on the walls with sculptures but with pictorial decorations situated at 1.50 from the ground: on the wall near the entrance door to the south cell, a scene is preserved that bears the sovereign in the act of giving an amphora to Isis, accompanied by Harpocrates. At the north side of the room, three doors giving access to as many cells (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, pp. 17-19). Only the central one, greater than the others, is decorated with reliefs on the architrave, surmounted by a double frame and decorated with a winged solar disk, and on the side jambs with texts and reliefs (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, pp. 43-120). Among the decorations, many parts of the building preserved graffiti more than 200 graffiti, some of which already recorded during the Italian investigations (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, pp. 121-145). According to the more recent studies on the complete group, they have probably been made by priests during the Greek and Roman frequentation of the temple (Dijkstra 2008, p. 98; p. 100). Finally, during the excavation four altars dedicated by dedicated by the Ptolemaic period have been found, likely placed not in situ (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, pp. 32-34).

Roman Period

There is not much information about the frequentation of the sanctuary in Roman times. When the pagan activities inside the temple ceased is hard to say. The last-dated inscription from the temple walls I attributed to the second century CE. If the cult continued after this period, however, without doubt in the fourth century it was ended and it seems probable that the temple remained empty for a long time before it was reused as a church (Dijkstra 2011, p. 415.

From an archaeological point of view, the only testimonies of the Roman period correspond to some erratic architectural blocks identified in the temple area during the investigations carried out by the Italian mission. According to Italian scholars, the temple of Isis does not correspond to the original archaeological context, but it is more likely that they come from another place in the city. It is not excluded, in fact, that their original provenance is the temple excavated in 1908 in the area north of the English church of the modern city and that they were transported to the temple of Isis during the excavations conducted by the Director of the Museum of Upper Egypt el Hetta in the sixties of the last century (Pernigotti, Bresciani 1978, p. 310; see also Von Pilgrim et alii 2004, p. 124; Dijkstra 2008, pp. 107-109).

Artifacts

Block with hieroglyphic inscription of Tiberius Emperor (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, p. 257-259, nn. 1-6); Block with hieroglyphic inscription of Neronis Emperor (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, p. 175, n. 30; p. 259, n. 7; Blocks with inscription of Roman period (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, pp. 175-177, nn. 31-32, pp. 261-263, nn. 9-15); Block with hieroglyphic inscription and decorations of uncertain chronology (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, pp. 177-255, nn. 33-231; pp. 263-301, nn. 16-112).

Late Antique Period

The Italian team investigation carried out at the temple of Isis between 1971-1972 identified traces of the reuse of the pagan building as church during Late Antiquity thanks to the discoveries of activity of damaging of the figures of the most ancient reliefs and the realization of Coptic crosses and new painted decorations with Christian subject. Other changes were also recognized in the consisting in adapting of the building structures to the new use of worship.

According to the reconstruction proposed by E. Bresciani and S. Pernigotti (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, pp. 38-41), the church occupied the hypostyle hall with a small apse (E) arranged in the opening of the door of the naos of the pagan temple, which was therefore excluded from Christian use. In fact, in this room there are no signs of damage to the internal relief depictions. They also believed that the two side cells could have been used as prothesis, the one to the north, and as diakonikon the one to the south. The church thus organized proved to correspond to the typology of the Danubian churches with an apse to the east, sacristies to the north and south, three naves and two entrances. Other interventions carried out on the pagan building concern the opening of breaches in the facade, the creation of more or less regular niches obtained in the walls of the pillared hall and some adaptations in the original flooring.

Very important are the attestations related to the presence of remains of frescoes with a Christian subject, that the Italian scholars propose to date in the sixth century BC. on the two central facades, opposite, of the pillars of the hypostyle hall (P I-II), located at about 1 m height from the floor. Although in a very degraded state of preservation, on the north pillar it was possible to recognize a female figure jewelled on the throne (probably the Virgin Mary), which perhaps supported a baby Jesus; on the sides of this figure were three saints standing. On the south pillar there was instead a series of figures of bearded saints standing and on the right an angel.

Other testimonies of the temple conversion as a church are the presence of apical crosses on the pilasters of the pillared hall, of a Coptic cross engraved on the north facade of the north pillar, below. On the south pillar (north face), below are two Coptic crosses engraved on a graffiti depicting a large, manned boat. Inside the side door (on the south side) three crosses are engraved, while a Coptic cross is in the centre of the wall between the door of the central cell and that of the north cell. The eight-petal daisy motif is also of Coptic origin, inscribed in a circle, on the south wall of the main hall (west side), to the right of the large entrance portal.

A different hypothesis regarding the pagan building conversion has been later proposed by P. Grossmann, who assumed that the main cella was used as church, as attested by the discovery of one of the Greek altars probably reused for the Christian celebrations (Grossmann 1994, p. 194).

As the different reconstructions were only assumed but never proved by systematic studies, in 2000-2003 a meticulous analysis of the testimonies and data from the building has been conducted by the Swiss-Egyptian mission that work at the site. Based on the analysis on the fresco fragments preserved on the pillars, the scholars believe that no more specific date can be given for their creation than between the sixth and the ninth centuries. If these murals belong to the original decoration of the church, the date of its foundation should be placed within this period (Dijkstra, Van Loon 2010). Thanks to the archaeological investigation and the study of the graffiti in their architectural and archaeological context, it has been possible to better determinate the different life stage of the building. In the first phase, starting in the Late Antique period, probably in the sixth century, the temple functioned as church. This use seems to continue also during the second phase, almost up to the ninth or tenth century, when some houses to the south of the temple started to occupied part of the space around and in front of the main entrance of the building. In the last period of life of the church, when the ground level was raised respect to the origins, a breach was opened on the façade of the building as provisional entrance. These research have confirmed that the space of the Late Antique church was the pillared hall, where the Greek altars were moved to be used during the cultic celebration. The area where the main altar stood, the presbyterium, was closed off by screens (cancelli), maybe not more than a meter high, as usual (Dijkstra 2008, pp. 99-106).

Architectural elements not in situ

Decorative Coptic Fragments (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, pp. 302-303, n. 1-10); Christian stelae to Jacob Patriarch with Greek inscription (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, p. 303, n. 11); Fragment of Christian stelae (Bresciani, Pernigotti 1978, p. 304, n. 12).

Unknown Church

Late Antique Period

From the information relating to the excavations conducted in 1907 for the construction of a building in the area north of the English church of the modern city (corresponding to the site of the present Coptic church), it is possible to know the discovery of a series of architectural and decorative blocks from Greek and Roman times, attributed to a pagan temple built by Ptolemy IV Philophator, originally stood in that area, later renewed by Roman Emperor Tiberius, Claudius and Trajan. Some architectural and statuary fragments showed signs of Christianization such as the presence of crosses carved in relief or the cancellation of the most ancient inscriptions. On these bases, it was possible to suppose the transformation of the pagan temple (so-called Temple of Ptolemy IV) into a church, a hypothesis also supported by the discovery of some capitals characterized by typological characteristics of the Byzantine era (PSBA 30, p. 78). However, according to the recent analysis proposed by J. Dijkstra, the blocks found in 1907 could not be attributed to any pagan temple present in the area, but rather to a church of unknown date built thanks to the reuse of material coming from different ancient monumental complex. According to the hypothesis of the scholar, the fact that the blocks belong to the same period as those pertinent to the constructions present in the sacred area of Elephantine could suggest their origin from this site, and in particular from the so-called temple X (Von Pilgrim et alii 2004, p. 124; Dijkstra 2008, pp. 107-109).

Church with Martyrdom and Baptistery (Area 6)

Late Antique Period

Blocks from a temple dating back to Ptolemy VIII were reused for the construction of the church. Three Egyptian stelae, one with the inscription visible, were reused as pavement slabs for the area in front of the baptistery.

An emergency excavation in area 6 (Kasr el-Hagar Street), in a site north of the wall that probably in Late Antiquity divided Syene in a northern and southern sector, brought to light the foundation of two structures built with reused block from a Ptolemaic temple. A baptistery was built at a later stage along the same street as the two buildings. It was equipped with a cross-shaped baptismal font, accessible by three steps. In front of the baptistery, a paved area with Egyptian stelae of granite reused, leads to a vaulted martyr’s tomb. At the end of VII c. CE the site changed its function and became a residential area until the 14th c. (Dijkstra 2008, pp. 109-110; Von Pilgrim et alii 2004, pp. 143-148; Von Pilgrim et alii 2006, pp. 253-264)

Bibliography

- Bernard, A. 1989. De Thèbes à Syène, Paris.

- E. Bresciani, e and S. Pernigotti. 1978. Assuan. Il tempio tolemaico di Isi, Pisa.

- Dijkstra, J.F.H. 2008. Philae and the end of ancient Egyptian religion. A religious study of religion transformation (298-642 CE), Leuven.

- Dijkstra, J. F.H. 2009 “Structuring Graffiti: The case of the temple of Isis at Aswan”, in Ägyptologische Tempeltagung: Structuring Religion (Leuven 28 Sept. – 1 Okt. 2005) edited by H. von Renè Preys, 77-93.Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Dijkstra, J.F.H. 2011. “The Fate of the temple in Late Antique Egypt”, in The Archaeology of Late Antique Paganism edite by L. Lavan and M. Mulryan, 389-436. Leiden.

- Dijkstra, J.F.H. 2012. Syene I: The Figural and Textual Graffiti from the Temple of Isis at Aswan. Mainz am Rhein.

- Dijkstra, J.F.H. 2013. Dijkstra, “The Christian Wall Paintings from the Temple of Isis at Aswan Revisited”, in Christianity and Monasticism in Aswan and Nubia edited by G. Gabra and H. Tekla, 137-156. Cairo.

- Dijkstra, J.F.H., and G.J.M. Van Loon. 2010. “A Church dedicated to the Virgin Mary in the Temple of Isis at Aswan?”, in ECA, 7, 10: 1-16.

- Grossmann, P. 1994. ‘Tempel als ort des konflikts in christlicher zeit”, in Le temple, lieu de conflict edited by P. Borgeaud et alii, 184-201. Leuven.

- Jaritz, H. 1985. Die Kirche des Heiligen Psoti vor der Stadtmauer von Assuan, Le Caire.

- Mariette, M. 1872. Monuments divers recueillis en Egypte et en Nubie, Paris.

- Müller, W. 2013. “Hellenistic Aswan”, in The First Cataract of the Nile. One Region - Diverse Perspectives, SDAIK 36, edited by D. Raue, S. Seidlmayer, and P. Speiser,123-135. Mainz 2013.

- PSBA 30. 1908. “Recent discoveries in Egypt”, in Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology, 30, 1908, 78.

- Von Pilgrim, C., K.C. Bruhn, and A. Kelany. 2004. “The town of Syene. Preliminary report on the 1st and 2nd season in Aswan”, in MDIK 60: 119-48.

- Von Pilgrim, C., K.C. Bruhn, J.H.F. Dijkstra, and J. Wininger. 2006. “The town of Syene. Preliminary report on the 3st and 4nd season in Aswan”, in MDIK 62: 215-277.

%20.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)