Introduction

Elephantine is an island in the Nile, with a small land extension (1.5 km north-south, 0.5 km east-west), which over the centuries has played an important strategic role, thanks to its location at the northern end of the first cataract, facing Aswan (Syene). Its name, both in Egyptian and in Greek translation, probably indicates the importance of the ivory trade amongst the different commercial goods managed by the island. During pharaonic era it was the capital of the Elephant nome, while during Ptolemaic and Roman periods it was reduced to a temple town and the administrative centre was transferred to Syene/Aswan, on the eastern riverbank. From an archaeological point of view, the site enjoys a particularly privileged condition: it has been occupied from Prehistoric times to Early Islamic period. There has been no overlap between the ancient site and the modern one, and the ancient remains, being located on a high ground, have been protected from the rise of Nile’s water.

The first excavations in the site were carried out by German (1906-1908) and French (1906-1909) missions. Then, after several excavations not well documented, from 1969 began the systematic research project led by the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo and the Swiss Institute for Architectural and Archaeological Research on Ancient Egypt in Cairo, still ongoing.

The ancient town developed at first on the ridge to the east of the island, where it has been identified the oldest settlement belonging to the Naqada II Period or about 3500 BCE. With the formation of the unified Egyptian state (ca. 3000 BCE), the town acquired importance as the southernmost border site and as the source for rare hard stones quarried in the neighborhood. It is highly probable that the towered fortress on the highest ground of the east isle near the riverbank was built during the I Dynasty (ca.3000/2950-2800 BCE). By the early II Dynasty (ca.2800-2650 BCE), the rest of the east isle was included within fortifications, thereby establishing the maximum extent of the town for the entire Old Kingdom. Administrative buildings, residential quarters, and various workshops have been spotted on the hill based on their distinctive plans and finds made in their ruins. During the Old Kingdom these buildings surrounded the first construction of the temple of Sotet, perhaps the seat of the deity from the period of Naqada III (ca. 3200 BCE). This was later joined by the temple of Khnum.

According to the results of the archaeological excavations, between the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom the temple of Satet has been repeatedly renewed, while under the kings Hatshepsut and Thutmosis III (ca. 1490-1440 BC) two new and larger temples were commissioned for both Khnum and Satet. During the XXVI Dynasty Khnum's precinct acquired an elaborately laid-out Nilometer at the riverbank and later, under the reign of King Amasis, a colonnade has been added in front of Satet's temple.

A new important restoration of the sacred area took place during the reign of Nectanebo I (380-362 BCE) and his successor Nectanebo II (360-340 BCE), planned a large, new precinct for the sanctuary’s proper and a small forecourt.

Even if during the Ptolemaic and Roman periods the administrative centre was moved from Elephantine to Syene, the town continued to be a prosperous centre in which the sacred area, and in particular the temple of Khnum represented a social, , and political institution. Between 305-30 BCE, the Ptolemies (in particular Ptolemy VI and PtolemyVIII) extended the project of the last pharaonic dynasty on the temple of Khnum, which was completed under Augustus with a large terrace on the riverbank. Roman times saw also a considerable enlargement of the sacred area and the construction of a monumental staircase along with a sanctuary near the town’s harbour.

During the Graeco-Roman period, there was a cemetery located between the Khnum and Satet Temples reserved for the burial of sacred rams. Its presence suggests that rams were kept in Khnum’s temple complex as living embodiments of the god at that time, if the practice was not, indeed, much order. Moreover, several houses and a dense block of two-storey structures of the Ptolemaic-Roman period has been identified to the north of the sanctuary. Always in the sacred area, archaeological research brought in light many architectural fragments pertaining to other two temples (so-called Temple X and Temple Y), but it has not been possible to determinate their original location inside the settlement’s wall.

From early fourth century, with the triumph of Christianity, the near city of Syene/Aswan definitively became the most important city of the region and Elephantine simultaneously lost its role of fortress, becoming its buildings and monuments a quarry of building materials.

Arabic sources of the early Middle Age report the existence of a monastery and two churches on the island. The remains of a small church of the early sixth century partially survive in the pronaos of the temple of Khnum. Differently, some other architectural elements from a large basilica were found in the centre of the town, suggesting that the church was not far away.

It is not known when exactly the town ceased to exist, but it seems possible that its complete abandonment occurred not later than thirteenth or fourteenth century.

Temple of Khnum

Pharaonic Period

A chapel dedicated to Khnum is documented in the site of the temple of Satet from the XI Dynasty (ca. 2100 BCE), even if the history of the cult of Khnum in the same precinct is probably older. By the XIII Dynasty Khnum was afforded of its own temple corresponding to a modest building located about 60 m south from the temple of Satet, in the centre of the city but at a higher level, and the two temples were connected by a staircase. The limestone fragments found in the trenches of later buildings have returned elements pertinent to an entrance portal decorated with cult scenes and a sacellum for the sacred boat, all ascribable to this dynasty.

At the time of Queen Hatshepsut, who ordered a new temple for Satet, the sanctuary was commissioned a comparably scaled structure for Khnum. The original location of this building of Queen Hatshepsut is not known but, at present, it appears most likely that it stood behind the back wall of the temple of Khnum, in the area later occupied by the columned hall of the later temple of II. The building may have faced north, toward the harbour area of the Elephantine (Report 2014-2015; Report 2015-2016; Report 2016-2017).

During Dynasty XVI, the sanctuary was considerably enlarged, and by Dynasty XX, the Khnum Temple greatly exceeded the one of Satet in area. Considering its many additions, and long life, very little remains of this building. In fact, only few architectural fragments are still visible on the site nowadays, while many other were reused in Ptolemaic-Roman structures or went missing when the sanctuary has been dismantled in Middle age. At the bottom of the temple hill, to the north-east side, the nilometer of the sanctuary was assembled in Dynasty XXVI and then renewed during Ptolemaic and Roman times. It resembles a sacred lake and probably replaced a similar installation that is mentioned in inscriptions of the Middle Kingdom.

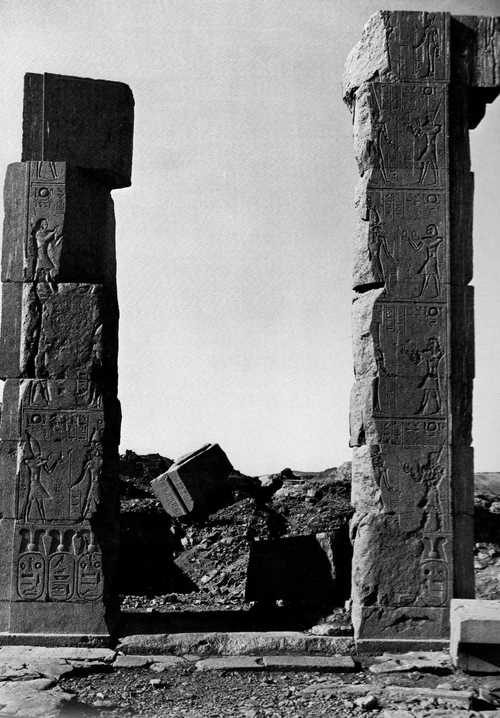

Lastly, Nectanebo I (380-362 BCE) renewed the Khnum’s temple and his successor, Nectanebo II (360-340 BCE), planned a large, new precinct for the sanctuary’s proper and a small forecourt. The temple was 28 m wide and 42 m long, with foundations about 3 m deep and crypts built into them. Archaeological research has allowed us to identify in the foundations of the temple of some relief blocks belonging to the temple house built during the New Kingdom (Report 2014-2015, pp. 12-15; Report 2015-2016). The blocks originate from at least two different buildings of early Thutmosid date. The first building was a small barque station built by Queen Hatshepsut for the processional barque of Khnum, while the second one was probably founded by Thutmosis I and finished or enlarged by Thutmosis II. The right doorpost of the portal still in situ supports a part of an architrave, composed of three stone courses and measured 2 m in height. Not in situ granite architectural elements from the facade, fragments of lintels and stones from the ceiling of interior rooms are what remain of the building today (Elephantine Guide 1998, pp. 29-32; pp. 37-38).

Hellenistic Period

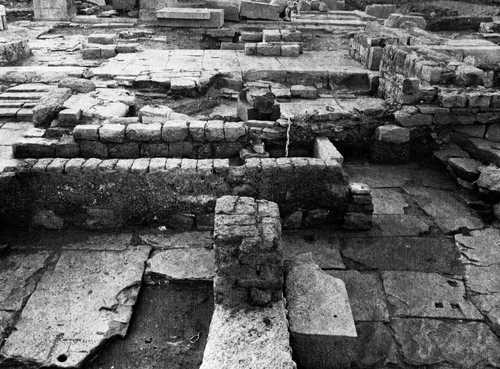

The landscape of the sacred area was rearranged in early Ptolemaic times. In particular, starting from 305-30 BCE it is attested a significant restoration of the temple of Khnum and the area relevant, with the construction of the pronaos in front of the temple, the large, monumental courtyard and their architectural decorations. Moreover, several small terrace walls had been built to compensate for the sloping ground level and a small ramp with flanking walls was built to lead up from a lower level in the west to a higher level in the east.

The central entrance of the temple erected by Nectanebo II was used in Ptolemaic period as central axis of the pronaos that was built in front of the sanctuary, served by a staircase to connect the two building. Recent research has also shown that numerous blocks belonging to the New Kingdom temple house were reused in the new construction. Respect to the central axis, a second entrance of the pronaos is located on the north side, and another one was probably on the opposite side. Characterized by three columns on each side of the main access, with the same number of pillars inside the hypostyle hall, the building once towered to a height of over 13 m, supporting a ceiling with astronomical decoration. Today only few columns of the hypostyle room and a huge granite gate leading to the inner sanctuary remain on the site, together with the corner of a lintel with an inscription on its inner face mentioning one of the Ptolemaic queens named Cleopatra. The main gate shows Alexander, the son of Alexander the Great, sacrificing to Khnum, Satis and Anukis, while examples of the temple's relief decoration are displayed to the left of the northeast subsidiary entrance, laid out in late Ptolemaic times (about 150 BCE). The first panel from the left shows fragments from the time of Ptolemy VI; the second through the fifth, those from the reign of Ptolemy VIII (Elephantine Guide 1998, pp. 34-37). Differently, the last one panels are from the Roman period. The archaeological excavations brought in light many architectural fragments probably pertaining to the twelve columns of the pronaos, characterized by different type of decoration (lily, palm, two versions of palmette and four versions of composite papyrus and palmette capitals) that still bear traces of colour ( Report 2005; Report 2007-2008). Moreover, the investigations still in progress are verifying that many blocks of the building reuse the structures of the temple house constructed during the New Kingdom.

The architectural studies in progress are also focusing on the different phases of the external courtyard of the temple, assuming that it was built for the first time in the Ptolemaic period and then enlarged in Roman times. It is probable that originally the portico was an empty space closed on four sides by a colonnade of which some column bases remain in situ. Preserved bases or emplacements in the pavement of the courtyard document the presence of statues and altars. In particular, four of the latter are set up nowadays on the south side. Their inscriptions name the Greet commanders of the town who dedicated them in the time of Ptolemy VI and Ptolemy VIII (ca. 150 BCE). Moreover, the two black column bases of Ramses II in the pavement served as points of orientation when the courtyard was laid out in the Ptolemaic period: the incised line that joins them bisects the gateway through the pylon and continues across the courtyard directly to the temple proper.

Part of the research carried out by the Swiss mission in the site comprises the study of architectural fragments found during the excavation of the temple and those preserved in the lapidarium. In fact, the large collection of fragments included in the register of representative remains of Ptolemaic and Roman decoration of the Khnum Temple. On the basis of the current results, it has been hypothesized the existence of accompanying buildings so far not identified within the temenos of the temple of Khnum. According to architectural and chronological definition of the fragments found, the hypothesis that these buildings existed derives mainly from the difficulty in determining the position of all the groups of fragments identified within the temple of Khnum. The ongoing archaeological investigation are also focusing on the area north of the temple of Khnum, occupied from the Ptolemaic period by a domestic neighbourhood where the houses of the sanctuary priests were located (Report 2007-2008).

### Roman Period

The archaeological investigations currently ongoing on the site are focusing on the recognition of transformation of the sanctuary carried out during the Roman period. Some decorative reliefs of the pronaos of the temple are certainly attributable to this period.

The main works carried out in the Roman phase that have been identified until now thanks to the archaeological research on the site refer to the enlargement of the external courtyard in early Roman times, probably during the reign of Augustus. The analysis conducted by Swiss mission on architectural fragments from the excavations in the temple area and those preserved in the lapidarium are still in progress. The first results seem to indicate renovations activities during the reign of Trajanus and Antoninus Pius, and some other interventions perhaps attributable to the reign of Hadrian. In particular, a complex of stones preserved in the lapidarium and consisting of small fragments of texts executed in sunken relief represents part of the early Roman decoration, probably of Augustus, sculpted on the walls of the building erected under the reign of Nectanebo II. The location and function of this text have not been determined thus far (Report 2007-2008).

Emperor Augustus is represented at the top of the third panel of the Ptolemaic pronaos, where are also documented fragments of frieze and cornice decoration from the time of Trajan.

Late Antique Period

- Chronology: Second half of the VI c. CE. On the chronological phases of the church, several hypotheses have been formulated by scholars. According to Grossmann 1980 (pp. 29-38) there were three phases: I. second half V/second half VI c. CE; II. second half VI c./VII c. CE; III. VII c. CE. The habitation in the forecourt could go up to the IX c. CE (Gempeler 1992, pp. 45-51; Arnold 2003, pp. 47, 77, 102-3).

From the first half of the fifth century until the first half of the sixth century the courtyard of the Khnum temple with its outer walls, still largely intact, were used as a fortified billet for a cohort sent at the town to protect the border of Roman Empire. The living quarter of the troops are still preserved on the south and south-west side of the courtyard. A little later, about at the end of the sixth century, in the area above the staircase of the Ptolemaic-Roman porticoes and to the north, a small church was built toward. In fact, by that time a civilian community has settled within the temple precinct, which had mostly fallen into ruin. In particular, in the north area of the temple are attested quarters of domestic buildings occupied both in Late Antique and Early Medieval period. The earliest occupation layer of this period, from the fifth and sixth centuries CE, was heavily damaged by the subsequent dismantling activities in the Khnum temple. During the Ninth Century parts of the buildings seem to have burnt down and afterwards renovated for a final time before being abandoned in the Tenth Century.

Since the IV c. CE, or earlier, the temple is no longer in use, as is proven by the abandonment of the housing complex reserved for religious personnel and the beginning of the plundering of architectural elements. However, the structure had already suffered damage, as evidenced by the traces of some fires lit in the pronaos and in the north-western porch, dating back to the III or IV c. CE. In the forecourt around fifty structures were built in the second quarter of the V c. CE., existing for about a century. According to Grossmann (1980, pp. 16-29) they were part of a military garrison, but Arnold (2003, pp. 20-21, 39-40) recently proposed that they could be housing for the poor. The temple’s dismantling process was determined by the different building needs for which construction materials were gradually requested. Blocks from the temple were reused for very different structures: Roman military camp, Late Antique houses built around the temple, Christian church and even the city walls of Syene/Aswan (cfr. Djkstra 2008, pp. 111-112).

The church was built in the temple’s pronaos, reusing some of its architectural elements. It is a small square structure equipped with four angle piers and probably covered by a dome vault. This type of square church is attested in Nubia and on Philae, but it is the only example in Egypt of structure with four angular pillars. On the northern side the wall stretched to the front wall of the pronaos, creating a deep niche open to the west. The baptistery was probably located in a northern room, while the presbytery was in the eastern corridor. Traces of cancelli were found between the two eastern corner pillars. A building located to the north of the church has been interpreted as a chapel, dated to the V/VI c. CE, or as a structure linked to a house (T 43) situated nort-east of the church. In one of the “chapel’s” room a semicircle of stone plates has been discovered, with a dense (ritual?) substance in the vicinity (Arnold 2003, p. 41; Djkstra 2008, p. 113, 119 note 148).

Basilica

- Chronology: Second half VI c. CE

The so-called “basilica” probably once stood in the centre of the town, as suggested by the findspots of a number of architectural elements (sandstone column bases, shafts, materials of red Aswan granite), used to reconstruct the church in the archaeological park of Elephantine (Elephantine Guide 1998, p. 47, VP21; Dijkstra 2008, pp. 118-119; Dijkstra 2011, p. 417). Not all the materials originally belonged to this structure, but probably to other constructions not preserved. See: Honroth, Rubensohn, Zucker 1910, p. 47; Grossmann 1980, p. 47. For further bibliography: Dijkstra 2008, p. 119, note 149.

Literary sources

The basilica has been identified with the church mentioned by Abu Salih, an Arab historian (XIII c.) in his commentary on Elephantine.

Harbour area: Church (?) near the Roman Staircase

In the harbour area of Elephantine, near a monumental staircase of Roman times, in 1985 a quay wall was discovered that was interpreted as the northern wall of a church, according to some evidences: the building orientation, which was similar to that of the church in the temple of Khnum; the presence of sandstone columns with crosses on the platform over the wall; crosses engraved, together with a “Coptic” inscription, on the wall (H. Jaritz in W. Kaiser et Al. Stadt und Tempel von Elephantine 13./14. Grabungsbericht, in MDIK, 43, 1987, p. 107; Dijkstra 2008, p. 114). The complete excavation of the wall, which took place between 200 and 2002, has allowed other data to be recovered and this interpretation to be slightly modified. The quay wall has certainly had a renovation during the VI c. CE, when it was reconstructed used almost exclusively blocks from the so-called temple Y, a roman structure dedicated to Osiris-Nesmeti that was supposed to be built nearby. On the quay walls M 1273-74 were found: 5 representations of boats, 4 Greek inscriptions (Dijkstra 2008, pp. 115-118, appendix 5, nn 5-8) and about 22 crosses incised, dated to the second half of VI or shortly after, but the recent excavations have excluded that these walls may belong to the north side of a church. Instead, it was hypothetically identified with a church a rectangular structure recognized above the platform (M 1276), of which 3 blocks are preserved. This church may have been built after the middle of the 6th c. CE, when the quay wall was renovated (Dijkstra 2008, p. 114-119). a granite base discovered in the vicinity and the planimetric similarities with the church in the temple of Khnum are considered clues in favour of this hypothesis. (S. Schnenberger in G. Dreyer et Al., Stadt und Tempel von Elephantine. 28./29./30. Grabungsbericht, in MDIK, 58, 2002, pp. 200-209).

Bibliography

- Andriolo, D., and S. Curto. 1998. “Catalogo delle chiese dell’Egitto”. Memorie della Accademia delle Scienze di Torino. 2. Classe di Scienze morali storiche e filologiche 5, 22: 42-412.

- Arnold, D. 2003. Elephantine XXX. Die Nachnutzung des Chnumtempelbezirks: Wohnbebauung der Spätantike und des Frühmittelalters, Mainz 2003.

- Bagnall, R.S., and D. Ratbone. 2004. Egypt: From Alexander to the Copts: An Archaeological and Historical Guide, London 2004.

- Dijkstra, J.H.F. 2008. Philae and the end of ancient Egyptian religion: a regional study of religious transformation (298 - 642 CE), Leuven 2008.

- Dijkstra, J.H.F. 2011. “The Fate of the Temples in Late Antique Egypt”, in The archaeology of late antique "paganism" edited by L. Lavan, and M. Mulryan, 389-436. Leiden-Boston.

- Elephantine Guide 1998: Elephantine. The Ancient Town. Official Guidebook of the German Institute of Archaeology – Cairo, Cairo 1998.

- Gempeler, R.D. 1992. Gempeler, Elephantine X. Die Keramik römischer bis früharabischer Zeit, Mainz.

- Grossmann, P. 1980. Elephantine II. Kirche und spätantike Hausanlagen im Chnumtempelhof: Beschreibung und typologische Untersuchung, Mainz.

- Grossmann. P. 2002. Grossmann, Christliche Architektur in Ägypten, Leiden.

- Honroth, W., O. Rubensohn, and F. Zucker. 1910. “Bericht über die Ausgrabungen auf Elephantine in den Jahren 1906 – 1908”, in ZÄS, 46: 14-61.

- Schweizerisches Institut für Ägyptische Bauforschung und Altertumskunde in Kairo. Elephantine. http://www.swissinst.ch/html/elephantine.html, accessed 23/10/2021.

- Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. Elephantine. https://www.dainst.org/it/projekt/-/project-display/25953, accessed 23/10/2021.

- Müller, M. 2016. “Among the Priests of Elephantine Island Elephantine Island Seen from Egyptian Sources”, in WO, 46: 213-243.

- Raue, D., C. von Pilgrim, F. Arnold, M. Bommas, J. Budka, J. Gresky, A. Kozak, P. Kopp, E. Laskowska-Kusztal, M. Schultz, and S.J. Seidlmayer. 2007-2008. Report on the 37th season of excavation and restoration on the island of Elephantine https://www.dainst.org/it/projekt/-/project-display/25953, accessed 23/10/2021.

- Seidlmayer, S.J., F. Arnold, J. Budka, R. Colman, J. Fayein, C. Jeuthe, E. Khalifa, F. Keshk, P. Kopp, W. Mayer, C. von Pilgrim, J. Sigl, M. Schröder, L.A. Warden, and N. Warner. 2014-2015. Report on the Excavations at Elephantine by the German Archaeological Institute and the Swiss Institute from autumn 2014 to spring 2015 https://www.dainst.org/it/projekt/-/project-display/25953, accessed 23/10/2021.

- Seidlmayer, S.J., F. Arnold, R. Bicker, R. Colman, D. Fritzsch, C. Jeuthe, E. Laskowska Krusztal, P. Kopp, M. Renzi, J.A. Roberson, J. Sigl, C. von Pilgrim, and L.A. Warden. 2015-2016. Report on the Excavations at Elephantine by the German Archaeological Institute and the Swiss Institute from autumn 2015 to summer 2016 https://www.dainst.org/it/projekt/-/project-display/25953, accessed 23/10/2021.

- Sigl, J., J. Budka, C. Jeuthe, E. Laskowska-Krusztal, P. Kopp, C. Malleson, M.K. Schröder, V. Steele, C. von Pilgrim, and L.A. Warden. 2016-2107. Report on the Excavations at Elephantine by the German Archaeological Institute and the Swiss Institute from autumn 2016 to summer 2017 https://www.dainst.org/it/projekt/-/project-display/25953, accessed 23/10/2021.

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(Elephantine%20Guide%201998%2C%20p.%2011%2C%20fig.1).jpg)

%20(Elephantine%20Guide%201998%2C%20p.%2013%2C%20fig.%202).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)